Offshore wind: One-stop Power Conversion

With the United States and China about to start their respective offshore wind build-ups, grid operators wondering about the efficiency of their turbines or the emissions-areas compliance of their wind-service vessels will be warmed to know there’s someone they can talk to. Yaskawa’s The Switch — a Japanese industrial giant’s European environmental tech business — is offering one-stop wind-energy shopping. As with shipping, you can order permanent magnet generators, drives and converters for your wind turbines. Take heart. The lingo is the same.

Yaskawa’s The Switch is well-placed to hybridize vessels or help convert power from wind turbines. In the U.S., they’ve quietly built up a $500 million business in low-voltage and medium-voltage drives, with some sales of solar inverters on the side.

Known in the North Sea for permanent magnet generators and frequency converters for wind turbines and marine power and propulsion, The Switch’s specialty is where the generator shaft meets the propeller shaft, with efficient drives for power outputs of from 0.5 kW to 11 MW.

Their marine permanent magnet machines can be used as gen sets or motors, and new drives come with configurations that download to a mobile phone and are a shipowner’s path to battery-powered hybridization. When Yaskawa bought the company in 2018, that was part of the allure of Wartsila’s power drives division, now called The Switch: the bought business offered scale, high-voltage drives, marine-market savvy and “green tech”. When acquired, The Switch had been focused on providing wind-turbine drives and marine shaft generators when Wartsila sold it to Yaskawa, which had smaller-capacity generators and a large range of industrial offerings, including its own drives.

Incredibly, permanent magnet generators and frequency converters for wind turbines and ships can be talked about together, if you like one-stop shopping: “In general, the technology is quite similar. But we customize the technology for the specific end application,” said The Switch’s director of product marketing for marine solutions, Ville Parpala, who didn’t mind indulging us.

“Some requirements are different for marine. For example, there are differences for the cooling system. Marine applications can use fresh water, for example, but wind needs closed-loop solutions. The generator speed is also different, and more redundancy is required in marine applications,” he says, not minding that we’re comparing towering wind turbines to wind-service shipping.

A similar discussion

“There are also different regulations, such as the strict classifications for marine. But in the end, marine and wind are very much alike. In wind, the goal is to put as much quality electricity into the grid (as possible). In marine, the goal is to slash operating costs and fuel consumption.”

Similarities aside, the timing of the company extending its global reach is perfect at this the dawn of US — and, it seems, Chinese — offshore wind expansion. By some estimates, the US offshore wind industry alone, still in the planning and acquisition stage, is a $70 billion market in-waiting. According to World Watch Institute, China is hoping to be 40 percent wind powered by 2050.

Yaskawa Environmental Energy, of which The Switch is a part, is the combination of a robotics savvy, mainly low-voltage industrial giant with a high-voltage marine power company which has delivered converters to over 6,000 wind turbines in China alone. The new Yaskawa company has also begun re-equipping part of the Norwegian offshore fleet with multiple-megawatt electrical drives while also kitting out the first, heavy-duty offshore-service vessels.

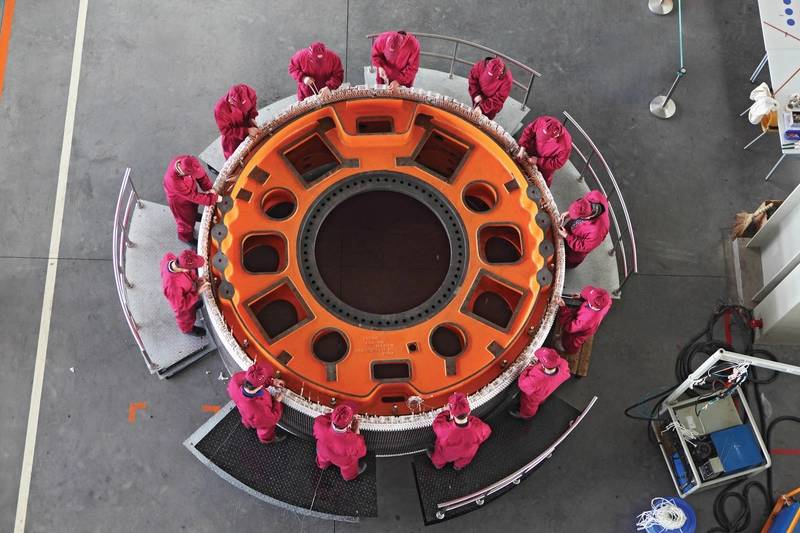

With the worldwide shift toward installing larger wind-turbines, a major wind-park and wind-carrier consideration in the US and China. The Switch — with its PM machines and converters ranging for applications from 500 kW to 8.0 MW — and the Yaskawa line of medium-voltage converters meet that coming challenge of scale. Optimal outputs: a wind-turbine permanent magnet generator at The Switch in Deyang. Image Courtesy Yaskawa’s The Switch

Optimal outputs: a wind-turbine permanent magnet generator at The Switch in Deyang. Image Courtesy Yaskawa’s The Switch

Marine scaleIn the first encounter with large offshore turbines off the US Eastern Seaboard, the site of Fred Olsen Wind Carrier’s 15,000 GT Brave Tern jack-up wind installation vessels wind installation vessel easily handling and installing turbines was a sobering sight for those who had seen the very first turbine assemblies with smaller vessels. Those first installs were bold, given the size of the vessels used.

“In marine, people’s lives depend on what you do,” said Parpala. “In wind, people rely on the quality of what you deliver. In a highly electrical world, it’s important to have high reliability at all times.”

As it happens, that pioneering Fred Olsen vessel — now at work in the U.K — was kitted out by The Switch. Apart from its ample specs and cranes, the Brave Tern employs dynamic positioning that allows the vessels to work around the wind turbines while not anchored.

In 2012 and 2013, The Switch delivered the drives for the propulsion machines of both Brave Tern and the Bold Tern. During the build by Lamprell (LAM.L) shipyard in Dubai, the three motors that came from another supplier were augmented with The Switch’s delivery of three 3,800 kW propulsor drives; three 2,700 kW tunnel thrusters and, in is understood, a DC Hub for each vessel.

Future wind-service vessels look set to face an increasing amount of environmental scrutiny and can expect to one day have to operate as hybrids. New wind players are often national grid managers involved in wind precisely for the green footprint. Even established players with roots in oil, like Equinor, have been known to insist on greener power from their marine suppliers.

“Our drives match turbine installation vessels very well,” Parpala said, explaining that specialized crew carrying vessels are generally too small for the company’s multi-megawatt equipment class.

“Generally, we have a good match whenever dynamic positioning is required. Our electrical drives and converters are ideal for any hybrid vessel, especially when they have DP2 or DP3, which is important for wind-supply vessels. Our drive products are already designed and delivered for this.

“The benefits of using our DC-Hub and (Electronic Bus Link, or EBLs) as well as our power drives is that you can use batteries for higher lifting capacity,” he says, suggesting again that future heavier turbine lifts might need that flexibility.

North Sea Giant

North Sea Shipping Company’s subsea construction vessel, North Sea Giant (built 2011), is a Yaskawa retrofit reference that recently made headlines for undergoing a conversion that would give it the kind of performance reliability and power efficiency future wind-service vessels will need.

When we visited Haugesund, the 18,000 GT North Sea Giant was doing sea trials with EBLs installed after undergoing a retrofit for its six, 5 MW engines, its DP3 with variable-speed drive and three hybridizing systems onboard that can deliver full ship power on one engine, if needed.

Like any offshore wind-turbine installation vessel or cable layer, the Giant needed redundancy. Tighter energy management rules demanded efficiency, hence the three DC hubs and EBLs installed for battery loops. An auxiliary generator added the variable speed. “It’s a gamechanger for running on a single engine (or DP 3 only),” said Cato Espero, Wärtsilä head of sales for Scandinavia. He adds that the North Sea Giant will cut two million liters per year of fuel costs for its owners, about as much as 2,000 cars per year. Its six engines can run as three, and its three battery packs are similar to the Fred Olsen wind-carrier jack-up vessel. “An electrical bus switch for their vessel cut the cost of operations and of fuel by 50 percent and allows its three different hybrid systems to work as one.”

In Norway, of course, government does offer funds for conversions to greener power, and so owners are not paying the full cost. It’s a national drive, and “Shipowners say the ships should be easy to convert to new fuel,” said Parpala.

China offering

While all of The Switch’s current customers for vessel-drive conversions are Norwegians, customers buying the company’s converters for wind turbines are largely Chinese and Danish. Their Chinese plants produce components for Chinese land-based wind turbines. The hope is to also get them buying drives for wind-service vessels and offshore wind turbines.

“The Chinese move fast to adopt new technology,” Parpala asserts, a confident nod to ramping up the Chinese wind energy value chain. “Since the start of our company in 2006, we have delivered 6,000 converters in China for onshore turbines. One of our key Chinese customers also has our converters offshore,” he says, adding, “but we have not yet produced any equipment for marine.”

The Switch had local manufacturing at several locations in China before the outfit was acquired by Yaskawa. In Hangzhou, The Switch’s people work with Finland-based contract manufacturer and system supplier, Scanfil, where they make full-power converters for wind. A factory in Lu’an makes converter components. Beijing and Hong Kong host The Switch sales and after-sales support offices.

Asked if floating wind farms like HyWind posed a different challenge, Parpala says, “Generally speaking, it doesn’t matter if (they’re) floating or fixed foundations, there is not much difference when it comes to the generator design. Some of our customers do have floating projects.”