Water Flows and Energy Grows

The Earth stores and preserves its resources for the future, and some of the Earth’s freshwater resources are kept in aquifers, underground, water-bearing rock formations that provide groundwater to wells and springs. The USGS Groundwater Resources Program studies the major aquifers across the Nation that includes assessments of groundwater availability and quality.

The Williston Basin, a large sedimentary basin located in the north-central United States and south-central Canada, is home to several regional aquifers containing limited groundwater resources with little to no recharge.

Groundwater in the Williston Basin

Covering nearly 135,000 square miles, the Williston Basin’s rock formations form a terrain that varies from ‘badland’ features to rolling, grass-covered hills. Within these formations there are shallow glacial and bedrock aquifers that extend no deeper than about 2,900 feet into the earth, creating a shallow and wide regional hydrogeologic framework of the uppermost principal aquifer systems in the United States and Canada.

The shallow glacial and bedrock aquifers are separated by thousands of feet from the deep saline water within the energy-producing formations. These deep formations were deposited in a shallow marine environment and the residing water has continued to dissolve minerals from the aquifer material, resulting in increasing salinity. The Bakken Formation contains some of the most saline water in the Nation.

Groundwater in this region is the primary (and sometimes only) source of drinking water. The water in the shallow glacial and bedrock aquifers is relatively fresh and potable, but sometimes considered ‘brackish’. The water quality often differs by the rock types and geological formation of each aquifer. In order to better understand the groundwater flow in the shallow glacial and bedrock aquifers in the Williston Basin, the USGS has created a conceptual model for the uppermost principal aquifer systems, using an approach that can be applicable to other major aquifers around the world.

The ins and outs of Groundwater in the Williston

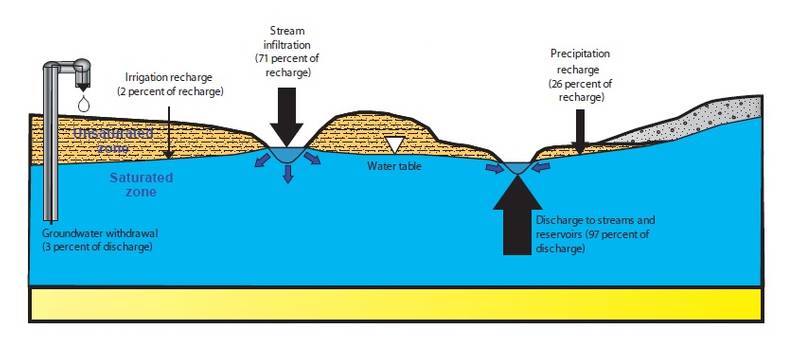

Water budgets are used to summarize the amount of water going in (groundwater recharge) and going out (groundwater discharge) of aquifer systems. The USGS recently developed a water budget for the uppermost principal aquifer systems of the Williston Basin.

The climate in the Williston Basin region is semiarid and annual precipitation (in the form of rain and snowfall) ranges from 11 inches in the western part to 21 inches in the eastern part. Precipitation that passes through the root zone in the ground from the land surface is defined as groundwater recharge. The main source of groundwater recharge in the Williston Basin is precipitation. Recent USGS reports estimate that groundwater recharge is 11-15% of precipitation, and is less than half an inch in most of the Williston Basin.

Almost all of this limited groundwater recharge is discharged to one of the streams or rivers in the Williston Basin. A much smaller amount is withdrawn by wells for irrigation and public-supply use.

Understanding Water Resources for Energy Use

The basin has been a leading source of domestic oil and gas production for more than 50 years. Today this region, which includes the well-known oil-producing Bakken and Three Forks Formations, is in the midst of a modern energy boom, driven by advances in oil and gas recovery technologies. These technologies have allowed access to previously untapped energy resources, but at the price of using large quantities of the limited surface water and shallow groundwater resources.

USGS scientists are conducting additional groundwater studies to determine if water quality of shallow glacial and bedrock aquifers could be affected by hydraulic fracturing or deep well injection activities, either from the chemicals used or the very saline produced water from the petroleum-bearing rock formations. The recently-published hydrogeologic framework and conceptual model are critical to understanding flow directions within and between the shallow aquifers.