The Decommissioning, Marine Life Connection

Data sharing and better understanding of how marine life interacts with manmade structures is the target for the next phase of the Insite program.

What to do with offshore structures is a sticky problem for oil companies, regulators and policy makers alike, as many structures are starting to cease production in the North Sea, where some fields have been producing oil and gas since the early 1970s.

Regulations, which include the OSPAR (Oslo Paris convention) state that a clear seabed should be left behind, once production has ceased, with some exceptions (platforms over a certain age and weight). But, some have argued that more should be left behind. However, little information has been available on which to base such decisions, which cost the public money (decommissioning is treated as an operational expense in the UK and as such is subject to tax relief) and could impact the environment (negatively or positively, where facilities are supporting increased marine life).

A program to help understand how offshore platforms and structures impact North Sea marine life – and therefore make more informed decisions on what to do with them at the end of their useful life – is hopping to address some of the questions.

The Insite Program (standing for INfluence of man-made Structures In The Ecosystem) initially ran from 2015-2017. Now, a second, five-year-long phase has started, thanks to some £7.6 million funding; £5 million from the UK’s Natural Environment Research Council, £2 million from the offshore industry and £600,000 from the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science.

Many fish species including common ling, Molva molva, make use of oil and gas infrastructure to hunt, forage and shelter. Image from Insite.

Many fish species including common ling, Molva molva, make use of oil and gas infrastructure to hunt, forage and shelter. Image from Insite.

Richard Heard, Insite Program director, told the Offshore Decommissioning Conference in St Andrews, late 2018: “This is about providing science for all stakeholders to try and understand what’s going on in the eco-system, so that we are informed and can make better decisions.”

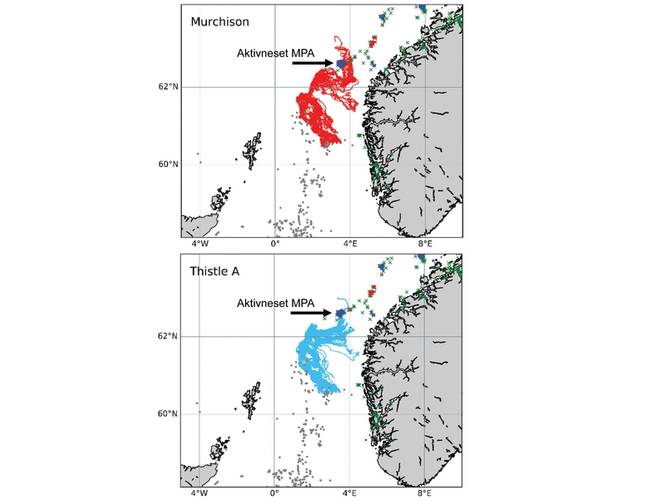

Significant findings of the first phase work, which involved 16 science institutes across Europe and eight oil major sponsors, included the discovery that the protected cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa on facilities in the northern North Sea (notably, Thistle A and the now derogated structure of Murchison) could potentially be supplying larvae that drift from these structures to natural coral ecosystems off Norway. Specifically, these two structures seem capable of supplying the Aktivneset marine protected area, which had been severely damaged by historical fisheries activity, and which is now beginning to recover. It could be that this is due to coral larvae drifting in from North Sea platforms.

Phase 1 of the program looked at the composition and biodiversity of marine life, from plankton to mammals. This included looking at plankton levels and distribution before oil exploration started up until now. It looked at connectivity and reef effects and aimed towards being able to model eco-systems to predict the effect of man-made structures.

While Phase 1 helped progress the understanding of the effects and connectivity of man-made structures in the North Sea ecosystem, some ground truthing is needed, says Heard, and more data is needed across the basin.

The Phase 2 work hopes to address some of these concerns. Its main objectives are to, one, understand the role of man-made structures as an inter-connected hard substrate network across the North Sea, two, understand the role of man-made structures as artificial reefs, and, three, provide ecological monitoring and assessment of man-made structures as whole systems in the North Sea ecosystem.

Heard says this work will be split into three threads: a data initiative, a science program and a technology program. A call will go out this year for science projects. The data initiative with rely on industry support and aims to gather and process existing data, develop protocols, collect and process new data, and develop data access products, eg. a portal. “We need to understand what data is out there. Is it relevant to science? How do we get it from operators?” says Heard.

Heard hopes that the industry will help by providing data, but also access to facilities for data collection, i.e. marine life surveys, sampling and monitoring, access to survey vessels and ROVs for monitoring, and the deployment and collection of data acquisition tools.

The technology program will seek out low-cost data acquisition systems and other technologies to enhance the data initiative.

Richard Heard, Insite Program director, told the Offshore Decommissioning Conference in St Andrews, late 2018: “This is about providing science for all stakeholders to try and understand what’s going on in the eco-system, so that we are informed and can make better decisions.”

Richard Heard, Insite Program director, told the Offshore Decommissioning Conference in St Andrews, late 2018: “This is about providing science for all stakeholders to try and understand what’s going on in the eco-system, so that we are informed and can make better decisions.”