Oil Price Crash has Silver Lining for Norway

Norway, Western Europe's top crude producer, looks set actually to benefit from the oil price crash as its energy sector is forced to relax its stranglehold over much of the economy and non-oil firms profit from more favourable business conditions.

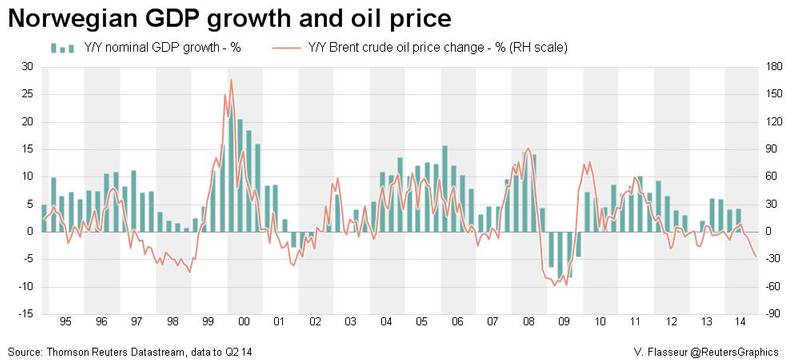

Although it generates almost a quarter of its GDP from oil and gas, about the same as Russia or Venezuela, Norway's economy remains surprisingly resilient, and even its oil industry has begun a readjustment towards lower costs that could extend the sector's lifetime.

While Russia faces recession and Saudi Arabia a budget deficit if crude prices hold at four-year lows of $78 per barrel, the impact on Norway will be limited as it benefits from a weaker currency, which will ease conditions in the labour market, slow down wage growth, and halt offshore cost inflation.

Norway is better placed than almost any other producer to deal with the current state of the oil market, cushioned against the crash by a mammoth fund of accumulated oil wealth worth $860 billion, or $170,000 per man, woman and child.

That means its budget, which only spends the investment returns on the accrued oil wealth, is unaffected, and the government could even increase spending without running up debt.

The low oil price could cut 1 to 2 percent from GDP over two years, economists say, but much of that will be made up by the rest of the economy.

Wiped Out

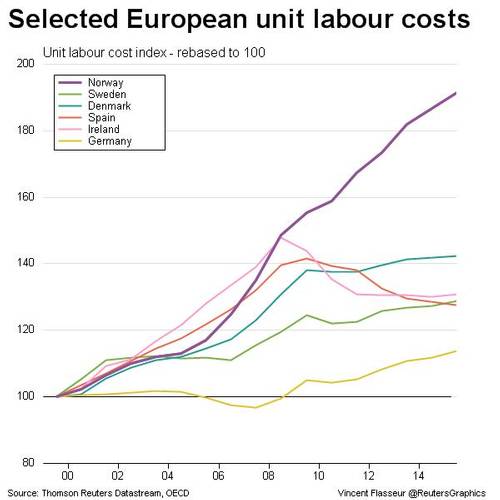

"The silver lining is not even hidden, it's quite obvious," says Harald Magnus Andreassen, an economist at Swedbank. "The currency's fall has wiped out seven years of extra wage inflation."

"This was a very convenient way for Norway to adjust the cost level," Andreassen said. "Had we done it the Greek way, with domestic devaluation like cutting wages, that would have been devastating for unemployment and consumption."

Norway's trade weighted currency has fallen more than 12 percent over the past two years, helping exporters without eating into consumption or seriously pushing up inflation.

Norway's GDP excluding the offshore sector is seen growing nearly three times as fast as the euro zone this year and its unemployment rate is less than 3 percent, a quarter of Europe's.

If people are worried about oil prices, it doesn't show. House prices are at record highs and Tesla's luxury Model S is one of the country's top-selling cars.

And neither is the government holding back with subsidies -- aid to dairy farmers in the Arctic is running at five times the European Union level.

Oil Boom

The oil boom has been blamed for hijacking the economy, pushing Norway's unit labour costs to twice the EU average. The booming oil sector has sucked the labour market dry, leaving many firms unable to find workers.

That could now change as oil prices fall and workers are no longer attracted into the energy sector.

"The cooling of the labour market will give us access to good and clever people and that's not a negative," says Arne Moegster, the CEO of fish farmer Austevoll.

The oil price crash may also revive some energy projects that have lain dormant due to rising costs.

"This is actually a good crisis to have," SAID Karl Johnny Hersvik, CEO of oil producer Det Norske. "We have seen immense increases in costs ... and the challenge is to be very rapid and proactive bringing them down again."

Statoil, Norway's top producer, has taken the lead, cutting engineering costs by telling contractors to combine work on projects.

Costs in the oil and gas sector, which only last year were expected to rise by a fifth over the next five years, are now seen as broadly flat over the period, according to the industry's lobby group.

The biggest drawback for the economy may be the lack of pressure on the government to rein in the budget, where spending of saved-up oil money will be $20 billion more than in 2007.

The government says some welfare spending is unsustainable and Norway must follow Sweden and Denmark in trimming the welfare state.

It has even a proposed a timid cut for next year but that has caused public uproar and hurt the government in opinion polls, possibly halting its reform efforts.

(By Balazs Koranyi and Ole Petter Skonnord; Additional reporting by Stine Jacobsen, Alister Doyle, and Joachim Dagenborg; Editing by Giles Elgood)