Offshore Wind: a Freshening Breeze?

July brought news about offshore wind. There was something for everyone: optimism, disappointment, and construction, too.

Finally, starting with Dominion Energy’s Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind Project, a joint venture with Danish wind developer Orsted is underway. True, this is a small project – just two wind turbines to be installed 27 miles east of Virginia Beach. But considering all the preceding hurdles, news about Dominion blew in as proverbial, hopeful fresh air. Surely, additional offshore wind construction news would quickly follow; news about a full line-up of projects ready to bust through interminable studies and studies of studies.

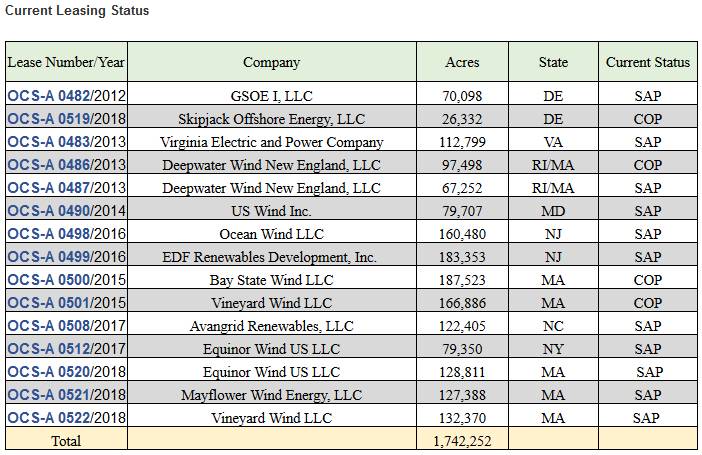

Indeed, there is a lot of offshore wind energy in the developmental pipeline. The table below shows wind energy areas (WEAs) from the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) website, part of the Department of Interior. BOEM leads all federal offshore energy siting and development in the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS), including wind.

Offshore Wind: harder to install than an oil platform

Importantly, a lease doesn’t mean there is a project is ready to go. In reality, there aren’t many projects advancing within most of the WEAs. There are a lot of project ideas. New York State, for example, on July 18, announced its selection of two ocean-based wind proposals, a selection in response to a high-profile solicitation last November. The projects, Empire Wind and Sunrise Wind, are planned for Atlantic Ocean WEAs OCS-A 512 and OCS-A 487, respectively.

Except for Block Island in Rhode Island, all the work on US offshore wind is still preliminary, really just a library. Actually, the studies themselves are the projects. This investigative work is quite advanced in one or two WEAs. In others, lease holders have requested extensions. In some cases, work has stopped.

Importantly, the Atlantic isn’t the only site with emerging projects. Icebreaker Wind is a six turbine, 20.7-megawatt offshore demonstration project in Lake Erie, eight miles from downtown Cleveland. It will be the first freshwater project in North America. It is winding down its regulatory and permitting requirements, awaiting final okay from the Ohio Power Siting Board. Construction is slated for 2022.

The project most likely to start after Dominion is Vineyard Wind, off Massachusetts, about 14 miles from the southeast corner of Martha’s Vineyard. Where power is concerned, this is the real deal: 800 MW, up to 100 offshore wind turbine generators.

A check on the federal Permitting Dashboard shows that Vineyard is tantalizingly close to completing seven major federal studies required to move to construction. Vineyard’s work is estimated to be complete by November 14, 2019. (See Table 2 for a list of the federal studies required from Vineyard.)

Table 2: Federal Studies Required to Complete Vineyard’s Federal Environmental Review & Permitting Process:

Study | Agency |

Construction and Operations Plan | Department of Interior (DOI) and BOEM |

Endangered Species Act (ESA) Consultation | DOI – Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS) |

Section 10 Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899 and Section 404 Clean Water Act | US Army Corps of Engineers |

ESA Consultation | Department of Commerce (DOC), and NOAA |

Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, Section 305 Essential Fish Habitat (EFH) Consultation | DOC and NOAA |

Incidental Take Authorization – DOC - NOAA/NMFS (National Marine Fisheries Service) | DOC, NOAA, NMFS |

Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) | DOI, BOEM |

(*) This Table is just an example. Some projects require additional federal studies.

Shortly after Dominion’s optimistic announcement, Vineyard Wind received troubling news: that BOEM would not have its final approval – a Record of Decision – for the company’s Environmental Impact Statement, expected on July 5. BOEM said its review was not complete, that it needed to push its deadline to August, later than expected, but still within the Agency’s promised two-year window.

On its website, Vineyard Wind presented a stoical reply, commenting that the delay was disappointing, but not surprising for a first-time project. Vineyard Wind needs the formal Record of Decision (ROD) by BOEM to set its construction team in motion. The logistics are daunting.

There was more bad news for Vineyard Wind. This summary has only focused on federal reviews. In fact, of course, there are state and local reviews. And in Edgartown, MA, on Martha’s Vineyard, the Edgartown Conservation Commission voted to deny Vineyard Wind the right to bury its transmission cables beneath Muskeget Channel, running through Nantucket Sound.

This unexpected “no” vote sent some difficult messages. Among many state governors and legislators offshore wind is unquestioned as a social and economic boon. At the local level, support is fractured. Vineyard Wind has since requested a superseding order from the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MA DEP) to overturn the Edgartown decision.

Residents in Easthampton, on Long Island, have raised similar, oppositional questions about the nearby South Fork project and its impact on Easthampton. Town officials may seek outside project review. New York’s Department of Environmental Conservation has filed a preliminary nine-page set of comments advising NY’s Public Service Commission that additional, extensive analysis is required before the project should be considered for a Certificate of Environmental Compatibility and Public Need.

In a message to BOEM, Vineyard Wind noted that “for a variety of reasons, it would be very challenging to move forward the Vineyard Wind 1 project in its current configuration if the final EIS is not issued within, approximately, the next four to six weeks” – or the end of August. MA DEP has up to 70 days to review Vineyard Wind’s request. A DEP spokesperson said the review will likely not take that long.

For Vineyard Wind, events may still turn as the company needs, but will that be timely? A Record of Decision is not an ending; it allows the next step within a much bigger process and sequence. A ROD confirmed in September could mean staying on schedule for work planned for November. A confirmation in November might be too late, for many reasons: weather challenges, marine mammal restrictions and, critically, too late to confirm contracts with specialty equipment suppliers and vessel operators.

All Logistics are Local

After BOEM’s decision, next steps aren’t much easier. Construction requires specialized vessels and equipment. Just how that might work is drawing a lot of brain power. The central challenge is that there are no American vessels available, as required by the Jones Act, for work in U.S. territory. It appears there are no vessels in the U.S. shipyard construction queue, either.

There are vessels available on the world market, but the Jones Act makes it difficult – almost impossible, save a waiver – for non-U.S. vessels to work in the United States. The Jones Act requires that all vessels working in US waters are American owned, American built and American crewed.

Emily Huggins Jones is an attorney with Squire Patton Boggs, based in Cleveland. She recently participated in a panel discussion, in Amsterdam, presented to European firms interested in the emerging US offshore wind market. Her advice: don’t expect a Jones Act waiver.

Huggins Jones predicts that an initial project will follow the protocol used for Block Island: the requisite, foreign equipment will be moved to a work site, but not to a U.S. port. However, it will be supplied by Jones Act compliant vessels and barges.

She said this deliberate distancing can work to get this new industry started. “Will it be the same in ten years?” she asks rhetorically. “Probably not,” she adds, “but we’ll likely be at a place where those issues have been worked out.” Huggins Jones said discussions are underway now at various corporate levels about whether it makes sense to have a pool of equipment, like the oil and gas industry. High costs are not the only problem. A bigger concern lurks in the background: whether there will be enough offshore wind work to justify those investments.

Separately, Icebreaker Wind officials (Lake Erie) are also thinking about the Jones Act. Dave Karpinksi is Icebreaker’s VP of Operations. He was asked about plans for vessels and equipment. Ideas include bringing in a heavy lift vessel through the St. Lawrence Seaway or modifying an available barge with a heavy crane. “We haven’t committed to one plan yet,” Karpinski said, adding, “We’ll need approximately 1 to 1½ years lead time.” Karpinski said a foreign heavy lift vessel would be Jones Act compliant because “we wouldn’t be coming into any U.S. port. This is how the Block Island Wind Farm turbines were installed.”

Separately, Orsted responded to questions about their marine strategy by saying in a prepared e-mail message, “While we won’t be using a Jones Act compliant vessel for the installation of the foundations and the turbines, because one does not exist, we will ensure that any construction activities are fully compliant with all relevant rules and regulations.”

Looking Ahead: one size does not fit all

On the world market, then, there is considerable doubt that the equipment available to take on the addition of concurrent U.S. offshore wind construction projects.

Jurgen de Prez is Commercial Director of Jack-Up Barge (J-UB), a Netherlands based company that provides self-elevating platforms for the global offshore energy market. De Prez was asked about supply and demand. Right now, he said, there is some overcapacity in jack-ups. But he expects that to change when new U.S. and Asian projects start, placing new demands on existing equipment working in the North Sea. Another upcoming issue, de Prez explained, is that increases in turbine capacity require jack-ups with longer legs and larger cranes. “In this emerging market segment,” de Prez noted, “there will be an undersupply.”

Equipment used by the oil and gas industry cannot install foundations and wind turbines. Right now, J-UB’s contracts are set about two years in advance. De Prez estimated industry lead time averages between one and a half and two years.

Offshore wind requires multiple specialized vessels. Each project is different, but De Prez said that, generally, a jack-up barge would be towed to the work site. Some jack-ups are outfitted with propulsion systems, allowing autonomous movement within the offshore windfarm. The exact vessel used depends on the phase of construction, de Prez explained. Foundations could be installed by a floating unit or a jack-up, but only a jack-up installs turbines. Cable lay vessels link it all together.

In a way, actually building an offshore wind farm isn’t the hardest part. The hardest part, really multiple parts, is starting a new industry almost from zero. It takes a lot of energy to reach critical mass – before it’s all linked together.

Only one thing is for certain today. When it comes to offshore wind – domestic offshore wind – getting these clean, green and renewable energy projects done is probably more difficult than getting permission to build a refinery. Opposition comes from many – sometimes surprising – quarters. The wind is coming; you can almost feel the breeze. The only question is: when?

This article first appeared in the September 2019 print edition of MarineNews magazine.