Methane Emission Reduction takes Center Stage of UN GHG Report

In four decades of climate negotiations, the world has focused intensely and exclusively on the most abundant climate-warming gas: carbon dioxide. This year, scientists are urging a focus on another potent greenhouse gas – methane – as the planet's best hope for staving off catastrophic global warming.

Countries must make "strong, rapid and sustained reductions" in methane emissions in addition to slashing CO2 emissions, scientists warn in a landmark report by the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1 released Monday.

The plea could cause consternation in countries opting for natural gas as a cleaner alternative to coal. It also could pose challenges for countries where agriculture and livestock, especially cattle, are important industries.

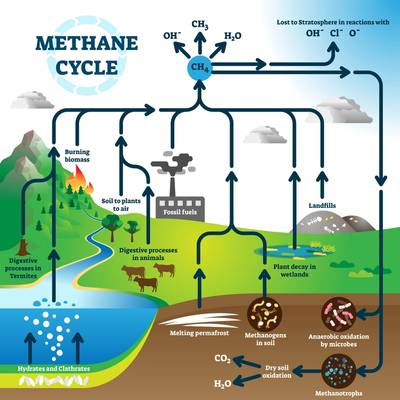

But while both methane and CO2 warm the atmosphere, the two greenhouse gases are not equal. A single CO2 molecule causes less warming than a methane molecule, but lingers for hundreds of years in the atmosphere whereas methane disappears within two decades.

The report puts "a lot of pressure on the world to step up its game on methane," said IPCC report reviewer Durwood Zaelke, president of the Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development in Washington, D.C.

“Cutting methane is the single biggest and fastest strategy for slowing down warming,” Zaelke said.

Why Methane, Why Now?

Today’s average global temperature is already 1.1C higher than the preindustrial average, thanks to emissions pumped into the air since the mid-1800s. But the world would have seen an additional 0.5C of warming, had skies not been filled with pollution reflecting some of the sun’s radiation back out into space, the report says.

As the world shifts away from fossil fuels and tackles air pollution, those aerosols will disappear – and temperatures could spike.

Quickly reducing methane could “counteract” this effect, while also improving air quality, said IPCC report summary author Maisa Rojas Corradi, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Chile.

On a global scale, methane emissions are responsible for around 30% of warming since the pre-industrial era, according to the United Nations.

But the role of methane, aerosols and other short-lived climate pollutants had not been discussed by the IPCC until now.

“The report draws attention to the immediate benefits of significant reductions in methane, both from an atmospheric concentration point of view, but also the co-benefits to human health from improved air quality,” said Jane Lubchenco, deputy director for climate and environment at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.

Methane Momentum

Updates in technology and recent research suggest that methane emissions from oil and gas production, landfills and livestock have likely been underestimated.

The report sends a loud signal to countries that produce and consume oil and gas that they need to incorporate “aggressive oil and gas methane reduction plans into their own climate strategies,” said Mark Brownstein, senior vice president of energy at Environmental Defense Fund.

Landfill and energy company emissions might be the easiest to tackle, he said. Large-scale agricultural methane is tougher, because scaled-up replacement technology does not exist.

The EU is proposing laws this year that will force oil and gas companies to monitor and report methane emissions and to repair any leaks.

The United States is expected to unveil methane regulations by September that are more stringent than rules issued by the Obama administration, which were then rolled back under former President Donald Trump.

The United States and the EU account for more than a third of global consumption of natural gas.

But major economies without strict regulations on oil and gas production or agriculture, such as Brazil and Russia, are also likely to be high methane emitters, said IPCC co-author Paulo Artaxo, an environmental physicist at University of Sao Paulo.

(Reuters)