While the oil and gas markets are starting to come to life, nearing the $50 per barrel mark, the future fate of floating production remains a mystery

The 20 year four-fold growth pattern in the world’s FPSO fleet stalls out in 2016 with a record number of FPSOs idle and available for redeployment – or perhaps to be forced into other uses, lay up or scrap. FPSO redeployments typically are far more complex, costly and risky than for (say) drillships and yet the need for redeploying idle FPSOs is now in the forefront of the industry like never before as FPSO owners also have to face the worst ever down market for their equipment and services.

Redeployments - The Early Days

In 1995 the Uisge Gorm FPSO, designed and built and operated by Bluewater in the Netherlands, entered service at the Fife field in the North Sea under a contract with Amerada Hess who were the operator of that development. Back then Dr. Rex Gaisford was development director for Amerada Hess in London and an enthusiast of FPSOs in their early days. He eloquently spoke of a world where FPSOs would move from producing one field to later producing at another field.

Worldwide the FPSO fleet totaled about 50 FPSOs in 1995.

Subsequent reality did not turn out quite as Dr. Gaisford forecast but the idea of FPSOs being easy to redeploy had taken root. After finishing at one field, the move of an FPSO to the next field often meant working at a seriously different water depth in different sea conditions with production and processing capabilities being required for a different grade of crude oil that usually had quite different ratios of gas and water present and all at different temperatures and pressures from the first field. So the FPSO usually had to be revamped big time.

Time and again it turned out that with realistic project engineering that the changes needed for an FPSO at a subsequent field became many and cost plenty. It was nothing like moving a drill ship from one well location for one operator to another location for another operator in another part of the world.

Redeployment can be hazardous to your financial health

Changes needed for redeployment have frequently turned out to be troublesome: difficult to manage within budget and often ran over on time. After Uisge Gorm, Bluewater built the Glas Dowr FPSO for another development in the North Sea, where it worked for not much more than a year before the two fields it produced from played out unexpectedly early. Still on contract, it stayed at a dock, warm stacked, for some years until finding a subsequent contract offshore South Africa in 2002. It was good equipment but from my own experience as a business developer back then, finding another contract for Glas Dowr was “challenging” to say the least. Street talk signaled that conversion costs for the new assignment ran over by about a 100 percent over planned budget (figures of $50 million reimbursed by oil company and $195 million total expended give an idea of the magnitude of work).

A few years later a novel kind of FPSO entered the market – ROUND instead of the traditional ship shape. Sevan, the designer and builder, had overcome many challenges in succeeding with this new design in a traditionally very conservative industry. One of their new generation of FPSOs (Voyageur) had to move from one field in 98 meters of water in the North Sea to another location in 90 meters of water in the North Sea which took a number of topsides changes (adding gas compression, gas lift and more water injection). Once again the overrun was approximately 100 percent (from about $90 to $170 million) but this time the FPSO contractor was still in its early days and financially strained. The end result was a change in the control of the FPSO contractor’s FPSO fleet as

Teekay (TK) took a position in the company in 2011.

Redeployments could thus become seriously hazardous to the financial health of FPSO owners. Redeployment of FPSOs had frequently become far more complex in recent years than had been expected in the early days. Rigorous management discipline in tackling these redeployments became crucial – even more so than in starting from scratch with an FPSO conversion or newbuild.

Industry Learns and the FPSO Fleet Grows

These trends became recognized among the more experienced of the FPSO community as FPSOs were redeployed. It was nothing near as simple as it may have appeared on the surface.

The redeployment business was well set forth in a presentation by SBM at an FPSO conference in Houston in 2012 which showed a number of examples of FPSOs being redeployed for a second or third time with one example (SBM’s FPSO II) being redeployed four times over the 20 year period of 1981-2001. 2012 was a relatively stable time in the FPSO market and SBM indicated a total of about 20 FPSOs being redeployed worldwide in the next five years.

Twenty years after the Uisge Gorm FPSO started producing in the North Sea, the world’s fleet of FPSOs had grown more than fourfold to something like 218, counting FPSOs that are operational plus these still under construction and these that are idle. In the last 10 years that growth has been more than twice as fast as for other types of Floating Production Systems such as semisubmersibles, Spars and TLPs, as the table below left shows.

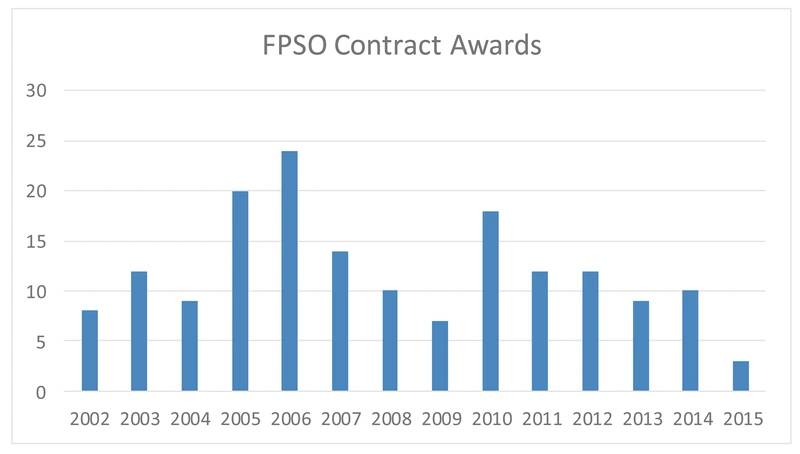

The FPSO fleet growth fluctuated from year to year as so often seen in the petroleum industry. The graph shows operator contract awards for the services of FPSOs every year since 2002, including contracts for the small number of redeployments each year in addition to the many conversions and newbuilds for new FPSO projects. (See chart)

Reconciling data in the table with the graph of FPSO contract awards, over the 10 year period of 2005-2015 an average of 2.1 percent of the fleet was retired each year for scrap or other uses. Market signals indicate retirals may become significantly higher in 2016.

The FPSO downturn in 2009 got people’s attention in the FPSO contractor community in Houston. I saw it firsthand that year when I flew from Houston to Singapore to chair and speak at the 2009 FPSO Congress. Leaving Houston the mood had been gloomy, while in Singapore the feeling was positive and buoyant. Singapore shipyards, engineering companies and vendors were all happily working through their healthy big backlogs of FPSO business. Fortunately for them 2010 was a great year for FPSO orders, and so the 2009 dip in FPSO contracts made little difference to them as their business levels saw little interruption. Today, seven years later, the FPSO communities in Houston and Singapore are both subdued.

If you look again at the graph of FPSO contracts, you’ll detect two downward trends, each fairly steady: in 2005-2009 and again during 2010-2015. It’s almost as if this signals a maturing and saturation in the market. But who knows?

As the last few years progressed the prospect of FPSOs becoming idle and available for redeployment evolved to no longer be a somewhat unusual “now and again” phenomenon but more of an anticipated process as FPSOs somewhere or another would reach the end of their service at their locations as the fields they served ended economic production. They would be released and be ready to move on, whether owned by an FPSO contractor or owned by an operator (ownership is split about half and half between contractor and operator for the world’s FPSO fleet).

It was often unclear at any particular point in time just when and how many FPSOs would become available for redeployment – field production economics and operators’ plans were often not widely discussed. But in a reasonably stable market – if ever that exists in the oilpatch – FPSOs would become available, some would be redeployed, some retired, and a somewhat steady turnover could be expected.

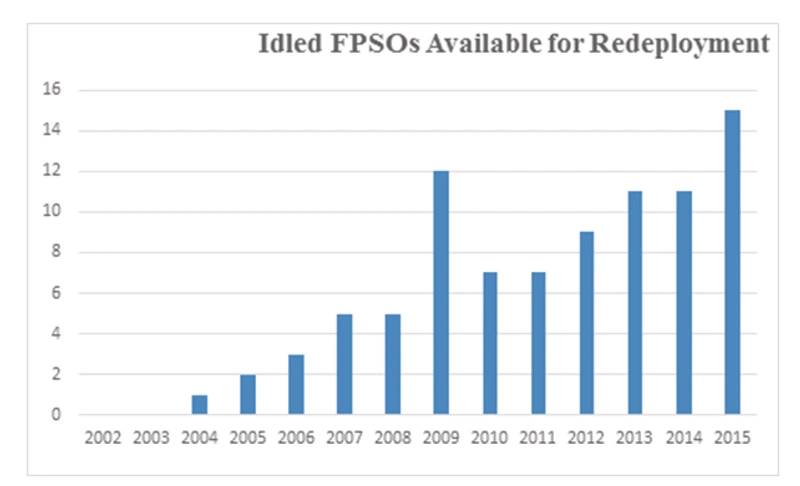

In a few lucky cases an FPSO employed by one operator might be used in a nearby field development operated by that same oil company. But most of the time an idled FPSO faced a lengthy period of being unemployment pending a new job - or retiral. New FPSO employment was traditionally slow and difficult to find - the same predicament that so many engineers and managers have experienced as they were laid off in the 2015-2016 downturn. The graph on “Idled FPSOs Available for Redeployment” gives the history.

Interestingly the last FPSO downturn in 2009 also saw an uptick of FPSOs idled, just like that shown for 2015.

Relative to the world fleet of FPSOs, the number of idled FPSOs has fluctuated year to year from a low of 0.8 percent to about 6.8 percent in 2009 and in 2015. Many expect that percentage to be seriously higher by year end 2016.

Today’s Dire FPSO Market

The pace of FPSO contracts had already slowed in 2015 to 3 after a total of 63 in the previous five years. The slide in crude oil prices that started in 3Q2014 was followed with a downturn in FPSO orders equally steep and in step with oil prices.

When 2016 arrived the situation was dire for operators who now were engaged in widespread cancellations and deferrals of projects, plus the selling of assets. New FPSO projects (conversions and newbuilds) had come virtually to a stop. Near term, operators talk of very few developments that will go ahead at current oil price levels. Added to that the economics of operations at tail end fields become quickly worse and operators think more quickly now about releasing FPSOs. Needless to say, prospects for new FPSOs contracts are at a record low.

As FPSO demand collapsed in 2015-2016, the scramble for redeployments grows

This year in May alone, announcements were made of the release of two FPSOs owned and operated by Bluewater: the Glas Dowr (leaving northwest Australia) and the Aoka Mizu (leaving UK Sector in North Sea), both proven high quality turret moored North Sea FPSOs. Regardless of the terms and settlements for the cancellation of these contracts, it means two more FPSOs on the market for redeployment. It sounds similar to the widespread cancellation of drillships in the offshore drilling business!

No one knows for sure how many more idled FPSOs will hit the market and face a similar limited redeployments possibilities. According to one knowledgeable observer (Fearnley Offshore) there may be a total of 22 FPSOs idled by year end 2016, offset perhaps by scrapping (four?) and possible redeployment (one or two?). In other words, something like 10 percent of the FPSO fleet may become idle by the end of 2016, representing an overhang in the market to challenge prospects for new FPSO orders.

Not so long ago in 2012 the prospects for redeployment might have been fair and often uncertain on timing, but not so today in 2016. FPSO contractors are sometimes reluctant to say exactly how many FPSOs they expect to have idle and available. It is not quite the open book seen in the offshore drilling industry where idled MODUs are identified and quickly become public knowledge.

The shutting down of new FPSO requirements plus so many existing FPSOs coming available has never happened on this scale before - truly uncharted waters. Talk of redeployments sounds to some as whistling in the dark in the current market, trying to avoid the possible necessities of layups and scrapping idle equipment of the kind that the drillers have already started to address.

On the E part of E&P business, it is easier for an operator to find productive employment for a drill ship than do so for an FPSO when on the P part of E&P, the prospect of finding an FPSO virtually ready right away to work at a new development would be wonderful but reality rarely seems to work that way. The need to get a production facility that does just what is needed leads back to contracting for a new FPSO, whether conversion or newbuild, rather than a redeployment.

Closing Thoughts

- All of this is not good news to the FPSO contractor community which hopes they do not have to manage their way through the kind of long term downturn that the drillers faced in 1986. And yet they see the potentially long delays before oil companies can see higher oil prices combined with some sense of stability to justify taking the risk in committing on multi billion dollar field investments that may employ FPSOs, whenever that might be, such is survival.

- Just a few years ago the redeployment situation was a relatively minor issue but in the current downturn it may prompt consideration of write downs on residual values on company balance sheets for both idled and employed FPSOs as a prudent measure in this market.

- As the offshore drillers have learned after more such brutal downturns, tough decisions are on the table about scrapping and lay up of FPSOs in the face of little or no redeployment prospects this year.

About the Author

Peter Lovie’s 49 years in engineering and management in the offshore industry have all been in Houston, the first 22 years on offshore drilling related business. Over the last 21 years Peter has become known as something of an industry authority on FPSOs, from his unusual combination of working on both the FPSO contractor and operator sides of the aisle as well as the necessary shuttle tanker side of it (Bluewater as BD Mgr, American Shuttle Tankers as VP, and Devon Energy (DVN) as Senior Advisor Floating Systems). He is known for his contributions leading to the first FPSO and shuttle tankers to enter service in GoM. Peter has been a frequent speaker and moderator at FPSO conferences worldwide and currently serves on the Advisory Board for Pennwell’s Topsides Platforms & Hulls conference.

He started in the oilfield with Cameron and The Offshore Company (now Transocean (RIG)), then founded an engineering company (ETA) with its introduction of a new generation of jackup drilling rigs in the 1970s, that were built in France, Singapore and Japan. That was followed by marketing and contracting MODU construction, then a 6 year stint in pioneering subsea processing.

Peter Lovie is author of 5 US patents and numerous technical papers. In the last two decades he held leadership roles in industry groups (DeepStar, SPE, Rice Global E&C Forum). Credentials include: Professional Engineer in Texas (PE), Project Management Professional (PMP) in 2009-2015 and Fellow of the Royal Institution of Naval Architects (FRINA). He earned his Master of Applied Mechanics degree at the University of Virginia where he was a Fulbright Scholar, and his B.Sc. in Civil Engineering from University of Glasgow in Scotland.

Currently Peter Lovie is an independent consultant. For more, including recent publications, please visit www.lovie.org

Acknowledgement

The author is indebted to Jens Heim of Fearnley Offshore who provided the FPSO fleet data that is used in the table and two graphs here to illustrate FPSO business trends.